Description:

About this item:

Editorial Reviews

Review:

4.9 out of 5

98.18% of customers are satisfied

5.0 out of 5 stars Near-Future of the Water Shortage

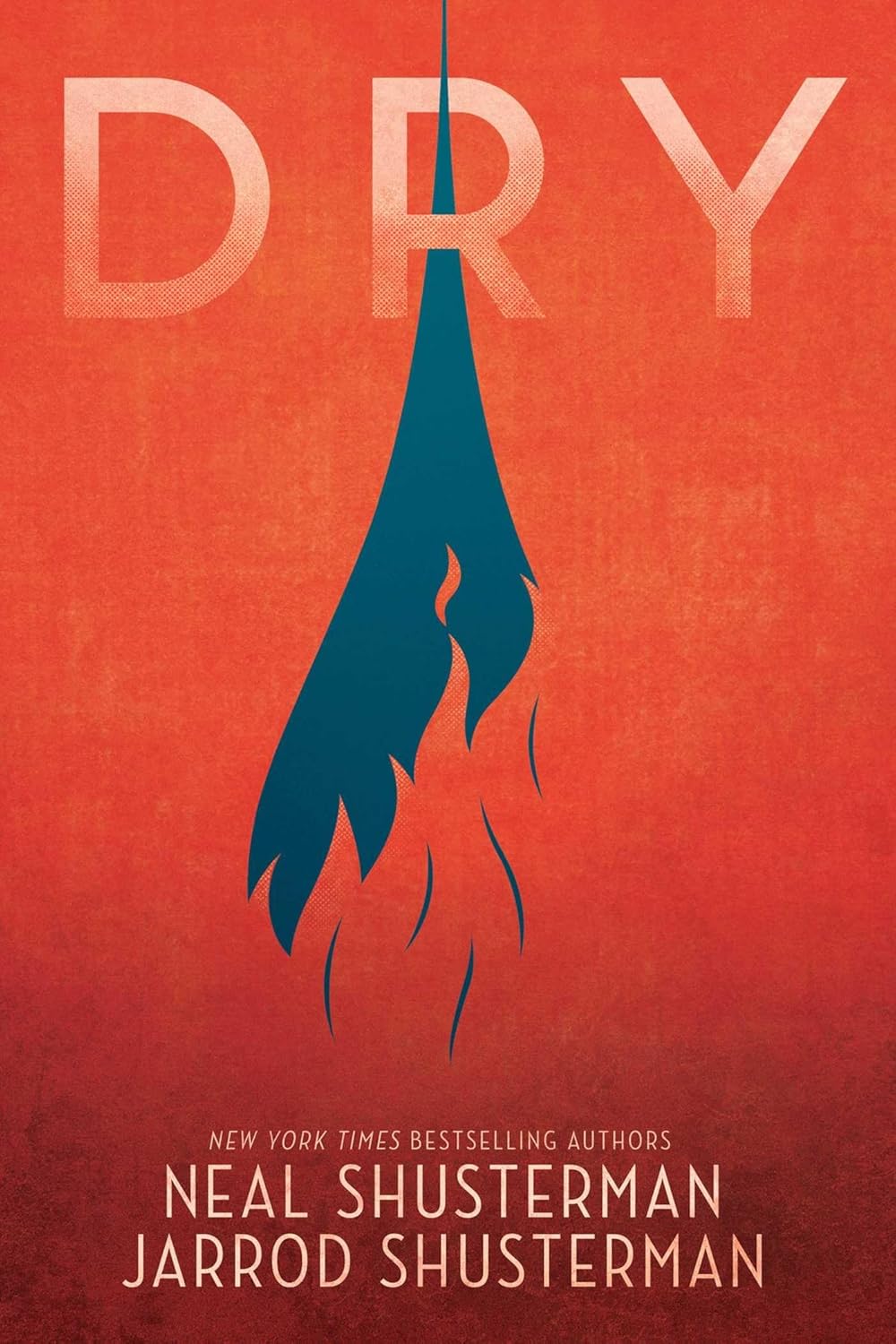

Neal Shusterman, author of Scythe and Thunderhead, and his son, Jarrod, come together to write Dry, a book that dives into a potential future due to California’s drought. If you look at the publication date of this blood entry, you might notice that only a few days ago here in California there was a massive downpour of rain. It was ironically funny that I was sitting in a classroom reading Dry while the water got so high it was literally pooling into the room through the door. After some discussion with friends, it sounds like enough rain came down and was collected to keep California going for years to come. But that’s not to say that the water will last forever. Many say the next world war might be over a natural resource, like clean, safe drinking water. While this book covers only the issue of California’s drought and a potential future the state might come to see in the near years to come, think about the catastrophe of just the level of state shown in this novel, and then bring it out to a global perspective. What is it was no longer just California that suffered from running out of clean, safe drinking water?One of the things I loved most about this book was the setting. It’s set in Orange County, California, and many of the high schools and other main structures are something I drive by often, or at least know about. This book really resonated with me in a visual way, and because of the closeness to my own home, made this event feel all the more real. When I was telling a friend about this book, when we were at Costco of all places, he was like, “Wait, when is this Tap-out happening?” I’m pretty sure I expressed that I was talking about a book, but he had pointed out the number of people purchasing water for the day, which brought flashes back from the scene at the beginning of the book when the taps first shut off: everyone had the idea to hit Costco and buy out all of their water, beverages, and ice!When we first start this book, we are in the perspective of Alyssa, seeing through her eyes first-hand what the shut-off of the water sounds like, feels like, and what emotions and fears that brings to her and her family. We are soon introduced to her strange waiting-for-the-apocalypse neighbor, Kelton. His family has their own electric grid, septic system, water reserve, and even a secret shelter in the woods called the Bug-Out, as if they were just biding their time for some catastrophic event to happen, knowing they are the one’s who are prepared to survive.Eventually, things take a turn for the worst when Alyssa’s parents go to the beach for potential sea-filtered water, along with a huge portion of the population. When they don’t return, Alyssa and her little brother, Garrett, become worried and aim to investigate. What they find at the beach is a bunch of discarded cell phone, destroyed machines, and even a potential body in the ocean. They cannot know what happened, but they can go find Alyssa’s uncle for help and advice.Along the way, they also meet Jacqui, an incredibly book-smart girl who appears street smart, but really just has a head-strong attitude. The four make their way in a stolen car to Alyssa’s uncle’s house, for he went to stay with his girlfriend in a gated community rumored to still have some water left. It’s eerily quiet there, and when they realize everyone is sick, or possibly even dead from contaminated water, they know it’s time to high-tail it out of there, but not without Uncle Basil’s truck, which he traded to some rich kid for a box of AguaViva, a bottled water company that the boy’s family owns.Henry, thinking he has one box of water left, doesn’t really know what the world of Orange County, California looks like outside the comfort of his own home. But his last box isn’t water; it’s a bunch of AguaViva brochures. But the others don’t know that. If he can hitch a ride with them, find a leadership position within their circle, and keep his secret hidden, perhaps he has a chance at survival too.As the characters grow more and more dehydrated, their chances of survival dwindle. Can working together even help them at this point?One of the things I love about the novel is the structure. Every so often, we get “Snapshots” of random people and the events surrounding them in different areas of Orange County, such at the Huntington Beach Power Plant, the John Wayne Airport, and the range County Water District. There’s so much going on with other people: trying to escape the state by car or plane (which is futile, considering the population density), seeking water by any means necessary as an act of survival, becoming on edge and fearing the worst of people (rather than the best), and ultimately the county looks like a zombie apocalypse happened. And in a way, it did. People act very differently when they are dehydrated enough that their lives might be at risk, and these “water-zombies” are a very real possibility, and do exist when the body does not get what it needs for survival.Another aspect I love about Shusterman’s books is that there is often a Barnes & Noble edition that comes with chapter-by-chapter annotations in the back of the books. While those of Dry feel a bit more about the choices made for the plot and characters (as opposed to Thunderhead, which revolves around political ideas as well), it is still always very interesting and fun to see why an author made the choice they did for their book. I like to read them after I finish each chapter, but be warned, there are some spoiler bits if you do that, so if you don’t want spoilers, save the annotations for after you finish the novel!This is an excellent novel that highlights a number of contemporary issues in California, that can also be relatable to the country, and world. This would make for an excellent classroom book for a current event or dystopian unit, as well as just to have for students to be able to access, because this fantastic book reverberates magnitudes about our society and humanity.P.S. Good news, everyone! The premise of Dry is so thrilling that a number of movie producers bid for the rights to the movie, with Paramount ultimately winning, and paying a nice sum for Neal and Jarrod to even write the script. This will be an utterly amazing film, and I can’t wait!

5.0 out of 5 stars Good read

I originally bought this book for my 12 year old son for his 7th grade summer reading list. Recommend by teachers. I decided to read it myself, and I think it was a good read. Definitely worth reading if you have some free time.

4.0 out of 5 stars YA Climate Change Adventure

I’m not sure if Dry is the very first YA novel focused on the potential chaos caused by a massive drought (here called the “Tap-Out” and set in southern California), but it’s definitely a well-written and engaging contribution to this niche subgenre.The protagonist Alyssa, a high school student, narrates the majority of the novel, sharing storytelling duties with Kelton—a neighbor and classmate whose family are survivalists, Jacqui—a brassy and intelligent rogue, and Henry—a haughty weasel who serves as the villain. Henry’s villainy, however, pales in comparison to the devastating effects of the drought and the reprehensible behavior it elicits from otherwise mild-mannered people.Devoid of many of the tropes that characterize contemporary YA, Dry chugs along for the first 300 pages or so, after which the narrative loses steam during what should have been the most harrowing part of the story. Nevertheless, it’s a worthwhile read.

5.0 out of 5 stars Amazing 🤩

This book was so good I wish I could read it for the first time again. Finished in a week with how much I wanted to just sit and read!

5.0 out of 5 stars A realistic look at the world running out of water

If there was ever a book that inspired me to stock up on water, this is the book. This was so realistic and really resonated with me. Neil Shusterman is really good about adding just the right amount of gritty details to make the story line pop out of the page. Having co-wrote this with his son, Neil Shusterman explores a potentially fatal future that will effect everyone.This book actually starts off with the acknowledgements, but this is done with good reason. This first line is dedicated to people who are fighting the effects of global warming. The water drought (also called the Tap-Out) that takes place in the book is never mentioned in the main story to be a direct result of global warming; but including it in the acknowledgements at the very beginning is a strong insinuation to how the world could potentially run out of water. This book had a "not in the too distant future" feel to it which made everything in the book feel both relevant and urgent.This book is told from multiple perspectives in alternating chapters, with a few news articles and external points of view also inserted to give a broader picture of what is happening outside the group we are following. The external media added a much broader dimension to what we saw and makes you realize how widespread the issue actually is. The multiple perspective are told by Alyssa (the average girl who lives in a middle class neighborhood) , Garret (Alyssa's little brother), Kelton (next door neighbor to Alyssa and Garret and also has a father who has been planning for Armageddon for years), Jacqui (a homeless girl who is really rough around the edges and used to surviving on her own) and Henry (a rich boy trying to capitalized off of everyone's lack of water). I loved how the multiple view points really added to the dimensions to the story and allowed us a glimpse into every socioeconomic status and how each were handing the Tap-Out in their own way.This story wasn't nonstop anarchy but it did convey how different people become when they are desperate to survive. People you thought you knew and people who are docile suddenly become aggressive strangers who are willing to do anything to make sure they don't die. We also find that a person's character is measured in desperate times. It was an interesting dynamic as it also assisted with character development and pushed some characters to become better people and others to do things they never thought they were capable of.I loved this story. I was less in love with this than I was with Scythe (also by Neil Shusterman), but it was more of a content issue than a quality issue. Dry was more of an apocalyptic contemporary whereas Scythe was more of a science fiction dystopian. Both were very enjoyable and very well written and I do highly recommend Dry. Dry was an amazing and very well constructed look at what happens when a renewable resource, like water becomes scarce. This was hard hitting and felt so realistic.

5.0 out of 5 stars Interesting Read

I enjoyed this book very much! Very realistic and even stressful at times!

Ok

Ok

I loved it!

A great book. I could not put it down. As a non-native speaker, I had no problems understanding the words. I highly recommend it and I also recommend keeping a water bottle nearby because you will be thirsty as hell. This book also could be a great addition to the EFL classroom☺️

Nice

Good ...useful for students

Dry

Encuentro que la trama engancha desde el principio, no se hace pesada y al mismo tiempo te hace reflexionar. Que más se puede pedir?

3 days to animal

How would we all behave and what would we be capable of doing facing a total water deficiency? An intriguing and scary story.

Visit the Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers Store

Dry

BHD702

Quantity:

Order today to get by

Free delivery on orders over BHD 20

Product origin: United States

Electrical items shipped from the US are by default considered to be 120v, unless stated otherwise in the product description. Contact Bolo support for voltage information of specific products. A step-up transformer is required to convert from 120v to 240v. All heating electrical items of 120v will be automatically cancelled.

Share with

Or share with link

https://www.bolo.bh/products/U1481481975